“Breaking up a monopoly and limiting their power—that’s what American democracy is supposed to be about.”

Senator Chap Petersen

By George Packer, The Atlantic. June 13th, 2023.

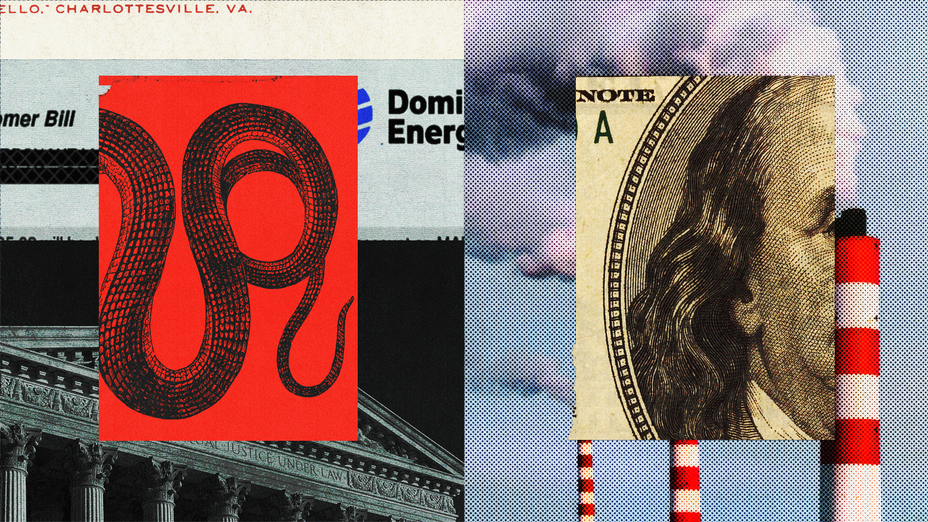

This is an old-fashioned story about monopoly power, dirty money, bipartisan corruption, consumer exploitation, and what Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis called “the curse of bigness.” It’s also the story of a recent victory over all those things—one that united the Sierra Club, Americans for Prosperity, Amazon, Google, and progressive and conservative members of the Virginia legislature. That story alone is rare enough to be worth telling. It might also have hopeful implications for our perpetually stuck politics.

Dominion Energy is a utility corporation that provides power to two-thirds of Virginians. The Dominion name and logo are inescapable: on monthly bills, utility trucks, and regional offices; on the glass headquarters that towers over Richmond and the nearby Dominion Energy Center for performing arts; at the Charity Classic golf tournament and all the other sports events and philanthropies that the utility sponsors. Dominion is regulated as a monopoly by the State Corporation Commission, or SCC, whose task is to set fair rates for the customer and a fair return for the utility. Dominion also provides more than $1 million a year in campaign gifts to Virginia politicians (the state places no limits on political contributions), including members of the general assembly, who pass the legislation that determines how the company is regulated. The main authors of these bills are Dominion’s lawyers and lobbyists.

In the past decade and a half, the general assembly passed a series of Dominion bills that gradually neutered the SCC, freed the utility’s rates from regulation, and allowed Dominion to overcharge Virginians (the term of art is overearn) by about $2 billion—by one reckoning, $3 billion—on their electric bills. Overrearnings were supposed to trigger refunds to customers, but instead big profits went to corporate executives (Thomas Farrell, who led Dominion for 15 years and died the day after he stepped down in 2021, averaged $14 million a year in compensation), to shareholders, and to the purchase of other companies. As for Dominion’s customers, their refunds amounted to less than a third of the company’s excess earnings.

This arrangement was entirely legal and scarcely noticed for years. It’s a glaring version of the corruption that underlies so much of American politics.

I recently sat on a park bench outside Richmond’s 18th-century neoclassical capitol while Albert Pollard, a former Democratic House delegate, now a lobbyist with the Virginia Poverty Law Center, explained how Dominion had managed this feat. In 2007, the legislature passed a sweeping law to regulate energy. If, in a biennial review, the SCC found that Dominion earned more than was legally allowed, customers would receive a partial refund. But Dominion lobbyists wrote provisions that locked in profits well above what the SCC authorized, and that prevented the SCC from lowering electric rates unless Dominion overcharged in two consecutive reviews.

With each new legislative session, Dominion introduced a bill with new accounting tricks (for example, accelerating the depreciation of storm-damage costs) that artificially lowered its earnings, thereby reducing refunds and preventing lower rates. Stephen Haner, a former lobbyist with the Newport News shipyard, was in the room in Richmond where these bills were negotiated. “Dominion’s game was always to make sure that the base rates never went down,” he told me, “and for a decade or longer, they never went down.”

Dominion’s lobbyists smothered the relevant section of the Virginia code with the kind of language that tells you that someone not in the room is going to get screwed:

In any triennial review proceeding conducted after December 31, 2017, upon the request of the utility, the Commission shall determine, prior to directing that 70 percent of earnings that are more than 70 basis points above the utility’s fair combined rate of return on its generation and distribution services for the test period or periods under review be credited to customer bills pursuant to subdivision 8 b, the aggregate level of prior capital investment that the Commission has approved other than those capital investments that the Commission has approved for recovery pursuant to a rate adjustment clause pursuant to subdivision 6 made by the utility during the test period or periods under review …

It would take too much space to quote the second half of the sentence.

“Dominion realized that legislators didn’t really know anything about utility regulation,” Pollard told me. “If it just took me 20 minutes to explain it to you, nobody’s going to get it.” The general assembly meets for only six or eight weeks every winter, and each session is flooded with at least 1,000 bills. “There are 100 legislative battles that you want to fight,” Pollard said, “and this is a hard one.” The only experts involved were Dominion’s dozens of lobbyists, which gave the corporation “a monopoly on information,” one legislator told me. “They kind of controlled the establishment on both sides.”

Meanwhile, Dominion behaved like a good corporate citizen, rushing linemen to fix local outages, giving discounts to low-income customers, funding social-justice groups, and touting investments in renewables. When a nonprofit organization hosted a training course in government ethics for newly elected officials, Dominion sponsored the event. While it was overcharging Virginians by hundreds of millions of dollars, it could claim that its electric rates remained below the national average. It sent checks to Democrats and Republicans alike; legislators of both parties voted for Dominion bills, often overwhelmingly, and governors of both parties signed them. “The amount of blind trust in Dominion cannot be overstated,” Will Cleveland, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, told me. “It’s honest corruption,” Haner, the shipyard lobbyist, said. “They do run a good company; they do provide a good product.” The utility was everywhere, like the railroad behemoth of Frank Norris’s 1901 novel, The Octopus.

Over the years, a few lonely legislators spoke up against Dominion. They tended to be outsiders, throwbacks. One was Lee Ware, a white-haired Republican member of the House of Delegates in rural central Virginia. The walls of his home library are lined with works of literature, philosophy, and theology, along with portraits of Confederate generals. When I visited, Ware was reading Jacques Barzun and the letters of Flannery O’Connor; his political models are Edmund Burke and Cicero. Ware actually read Dominion’s bills, and for years he was the only Republican to speak and vote against them consistently. “It became evident to me that Dominion was putting their thumb on the scale on their own behalf,” he said, in a way that must be called “courtly.” “It just over time became evident that this was unseemly.”

And there was Chap Petersen, a bow-tied Democratic senator from Northern Virginia, who angered progressives by opposing an assault-weapons ban and the name change of the Washington Redskins. But Petersen introduced bills, going back to 2008, for renewable energy and against Dominion’s growing domination that colleagues in the general assembly, including other Democrats, voted down. “I got into it because nobody else was doing it, and it was challenging intellectually,” Petersen told me. “Breaking up a monopoly and limiting their power—that’s what American democracy is supposed to be about.”

In 2015, the Obama administration announced the Clean Power Plan—new rules to limit carbon pollution from power plants. Ostensibly to protect customers from the costs of the plan’s implementation, Dominion wrote a bill that froze rates and suspended the SCC’s oversight until 2022. But energy costs were entering a steep decline, and the real effect of the rate freeze was to head off lower rates for customers while allowing the monopoly to regulate itself, pad its profits with new investments, and still retain the right to ask for rate increases. Nearly all Republicans and most Democrats voted for the bill, and Governor Terry McAuliffe quickly signed it. Members of the SCC, watching as their authority was stripped away, joked that they needed their own political-action committee to buy off legislators. (A later law returned limited oversight to the SCC and a $200-million refund to customers.)

The election of Donald Trump doomed the Clean Power Plan. At the end of 2016, with the whole issue moot, Pollard, at the Virginia Poverty Law Center, called Petersen and told him, “There’s no reason for the rate freeze anymore.” The next month, Petersen filed a bill to repeal the freeze, but it was immediately crushed, with most Democrats and Republicans again voting Dominion’s way. So was another bill Petersen introduced that would have prohibited regulated monopolies from making campaign contributions. Still, something began to shift in Richmond. “When they passed the rate freeze,” Pollard said, “they finally overreached.” Advocates, reporters, and elected officials began calling attention to the corrupt deal between the utility and the legislature.

The year 2017 marked a turning point in Virginia politics. A far-right rally in Charlottesville that August turned lethal when a neo-Nazi plowed his car into a crowd of counterdemonstrators, killing a young woman. A man named Brennan Gilmore, who lives with his dog in the woods outside Charlottesville, happened to record the murder. Gilmore is a bluegrass musician and bowhunter from Rockbridge County who served with the State Department in war zones such as Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic. When Gilmore’s video went public, Alex Jones, the professional liar and conspiracist, whipped up an online campaign to portray him as a CIA agent plotting to overthrow Trump. (Last year, after Gilmore sued for defamation, Jones agreed to pay him $50,000 and admit liability.)

In 2017, Gilmore was on leave from the Foreign Service (he has since retired) to work for the gubernatorial campaign of Tom Perriello, a Democratic former congressman from Charlottesville. The campaign took on Dominion over the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, its proposed gas pipeline through the Blue Ridge Mountains. Opposition to the pipeline united property-rights libertarians, environmentalists, hunters, and climate activists, and Dominion eventually had to cancel the project. Though Perriello lost in the Democratic primary to the reliably pro-Dominion Ralph Northam, who was elected governor that November, the pipeline controversy, the Dominion giveaway bills, the Charlottesville murder, and the Trump presidency all combined in two successive elections to bring to the general assembly a wave of younger Democrats who were less likely than their older colleagues to jump at the monopoly’s command.

One of them was Sally Hudson, a University of Virginia statistics professor in her early 30s, who volunteered for Perriello in 2017 and was elected to the House of Delegates in 2019. Hudson comes from Nebraska, the only state with fully public power, and her “political north star” is the prairie progressive Senator George Norris, who fought for it in the 1920s and ’30s. “For most people in Richmond, corruption is like shag carpeting,” Hudson told me. “Eventually, you stop seeing it at all. But if you’re brand-new to the building and you walk in, it’s all you can see. It’s everywhere, and it’s filthy, and it’s gotta go.”

Hudson was at home in Charlottesville when neo-Nazis marched past her house. She came to believe that the fever running through American politics was fed by corruption, and that Dominion was both a cause and a symptom of democratic decay: “Violent extremism is one of the downstream consequences of the corruption that manifests in corporate capture of the legislature, and gerrymandering, and everything that prevents public servants from being accountable to real people.”

During his campaign for governor, Perriello introduced Gilmore to a local hedge-fund manager named Michael Bills. A longtime environmentalist and “climate hawk,” Bills made a lot of money on Wall Street (“I am definitely not a billionaire,” he told me. “It’s not close. I have more than $100 million”) before returning home to Virginia to raise his four children. “I have been net carbon positive for 15 years,” Bills said when I visited his 140-acre estate outside Charlottesville, with a fine view of the Blue Ridge. He is meticulous in all things, including the planting of thousands of native hardwoods for carbon sequestration. “As of a year ago, I am energy positive. As of next month, I will have no carbon production in my house and property other than a tractor and two other pieces of machinery.” Bills first ran afoul of Dominion when he wanted to install solar panels on his barn and the utility made it extremely difficult. In 2021 the Sierra Club gave Dominion a “D” in the transition to renewable energy, and Virginia lags more than half the country in renewable usage.

In 2018, Bills researched Dominion’s political giving—a little more than $1 million a year over the previous decade—and came away unimpressed. “Not a lot of dollars,” he told me, given the corporation’s large overearnings, even throwing in another million annually for philanthropy. He began to think: What if somebody else—“me, and I could”—gave that money instead? “A couple million dollars a year, I could do.” Bills and Gilmore began to discuss a way to loosen Dominion’s grip on the legislature and energy markets—which Bills calls “morally corrupt” but perfectly legal—by offsetting its donations. In 2018 they started an organization called Clean Virginia, advocating for renewable energy and good government. Thus far Bills has distributed $20 million to scores of Virginia legislators. Clean Virginia’s only condition is that candidates complete a questionnaire and agree not to accept money from monopolies such as Dominion.

No one I spoke with liked the idea of a plutocrat’s money replacing a monopoly’s. Bills himself didn’t like it. “It’s not right,” he said. “I would be thrilled if there was a system that precluded someone like myself from doing that.” To Bills’s detractors in Richmond, he is the “Soros of Charlottesville.” A Dominion executive suggested to me that Bills wants a deregulated energy market in order to profit as an investor. But Creigh Deeds, a Democrat who has served in the Senate for more than two decades and stopped taking Dominion money in 2017, told me that Bills “has freed a lot of people to vote their conscience, on both sides of the aisle.”

The issue of unregulated monopoly doesn’t neatly divide politicians along right-left lines. Most of Clean Virginia’s recipients have been Democrats, but a few have been rural Republicans, including, for a time, Senator Amanda Chase, who calls herself “Trump in heels.” Bills told me that the organization’s “hardest fight” was against Richard Saslaw, the leader of the Senate Democrats for the past quarter century, and a Dominion ally who has taken $660,000 of its money. Tom Perriello framed the issue as a contest between “the corporate crowd” and “people across the political spectrum who believe that the system has been rigged against them.” Delegate Lee Ware, the longtime Republican critic of Dominion, spoke of “the sense that Big Tech, Big Pharma, Big Insurance, big banks that are too big to fail—these behemoths are in control of our lives, and the ordinary citizen says, ‘Who speaks for me?’” It’s a populist cause, but one that recalls the populism of the 1890s.

Bills and Brennan did not expect to see Dominion’s lock broken until 2025. But during the recent legislative session, which ended in late February, a small revolution took place.

Dominion approached the session as if it could continue to write its own legislation. While offering concessions to its growing number of critics—among them Dominion’s own investors—the utility’s latest bill would have raised its allowed profit margin by almost a full percent, resulting in billions of dollars in new earnings over the coming years. Dominion’s stock had fallen sharply, and the corporation warned that it might become a takeover target without the new bill. But Dominion hadn’t noticed that Richmond’s shag carpet was starting to be ripped out.

Two election cycles and Michael Bills’s money had brought dozens of Democrats to the general assembly who were prepared to oppose the utility. And Virginia’s new Republican governor, Glenn Youngkin, owed Dominion nothing. In 2021 its executives had tried to elect his Democratic opponent, Terry McAuliffe, by depressing the rural Republican vote with $200,000 or more in dark-money Facebook ads that portrayed Youngkin as weak on gun rights. (Dominion later said it hadn’t properly vetted the PAC that ran the ads.) In his State of the Commonwealth speech in January, Youngkin came out for “legislation to end the rapidly rising electricity rates that are hurting families and making businesses less competitive.” A Republican governor was taking aim at Dominion.

At a steak fry, Albert Pollard told me, Youngkin brought up his career as an investment executive. “I dealt with a lot of utilities in my private life,” the governor said to Pollard, “and when I don’t understand something, I just kind of know it’s not a good deal for the rate payer.” As Pollard put it to me: “What you ironically have is two very savvy investors who understood what a good deal Dominion had—and that’s Michael Bills and Glenn Youngkin.”

A different bill began to make its way through the general assembly—one to restore the SCC’s power to regulate the utility and set electric rates going forward. Its chief sponsors were the House Republican Lee Ware and, in the Senate, Democrats Creigh Deeds and Jennifer McClellan (who has since become the first Black woman ever elected to Congress from Virginia). In 2015, McClellan had voted for Dominion’s “rate freeze” bill. “A lot of us kind of had buyer’s remorse on that,” she told me. With the pandemic and then spiraling inflation, “I saw my constituents were hurting economically across the board, and I knew that one reason is that Dominion’s rates were artificially high and the SCC couldn’t do anything about it.”

A simple clarity, brought on by shifting incentives and the herd mind of elected officials, broke over Richmond’s capitol: The issue was excessive rates and unregulated monopoly. “They were without any friends for the first time,” Haner, the former shipyard lobbyist, told me. Amazon and Google, among the state’s largest energy consumers, came out against Dominion’s bill. So did the Virginia Manufacturers Association and the Koch-funded Americans for Prosperity. Greg Habeeb, a Republican former House delegate and current lobbyist, who agreed to work for Clean Virginia on the grounds that “it’s a very conservative position to say there ought to be a way for citizens to hold the powerful accountable,” asked Republican legislators: “Why would you ever pick the side of the one utility over literally everybody?”

Richmond finally turned against Dominion. On February 25, the last day of the session, a reform bill passed the general assembly almost unanimously.

I asked Bill Murray, a senior vice president at Dominion, who has guided the company’s legislative policy since 2007, why a Dominion bill finally lost. He looked at me quizzically. “What bill lost?” he asked. “Help me on this.” The utility felt “very good about how things had turned out.” He quoted his favorite president, John F. Kennedy: “Victory has a hundred fathers; defeat is an orphan.” Murray took this to mean that credit for a good thing can be widely distributed. But Kennedy, who said it right after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, meant that no one wants to admit responsibility for failure.

For now, unlimited money continues to corrupt state politics. (Clean Virginia’s next cause will be campaign-finance reform.) But this old-fashioned story has some wider political implications. Combat corporate money, and elected officials may be more likely to vote in the public interest. Argue about monopoly and corruption instead of race and sexuality, and unlikely allies will work together to solve problems. “At the end of the day, economic security trumps culture-war issues,” Gilmore said. “If you ask a rural Republican family, ‘Would you rather have more money in your pocket or go to an anti-trans rally?,’ they’re going to choose economic security.” Perriello put it this way: “Whichever party is able to show that it is fighting for the everyday person against rigged systems is going to win.”

I want to believe this is true, but I don’t know that it is. American politics over the past few decades says otherwise, and the script of the next election is already soul-killingly familiar: Republican candidates compete to excite their voters by crushing the “woke” left, while Democrats cry foul and play along. But an election modeled on the Dominion battle, about an economy that consolidates ever more money and power in ever fewer hands—that would be an election worth having.

George Packer is a staff writer at The Atlantic. See the original article here.